From the vantage point of Earth, M87’s black hole is smaller than the edge of a dime in Los Angeles as seen from Boston. Despite their brightness, even the largest black holes are tiny in the sky because they are so far away. Though this disk shines brighter than nearly any other object in the universe, it’s tricky to capture in an image.

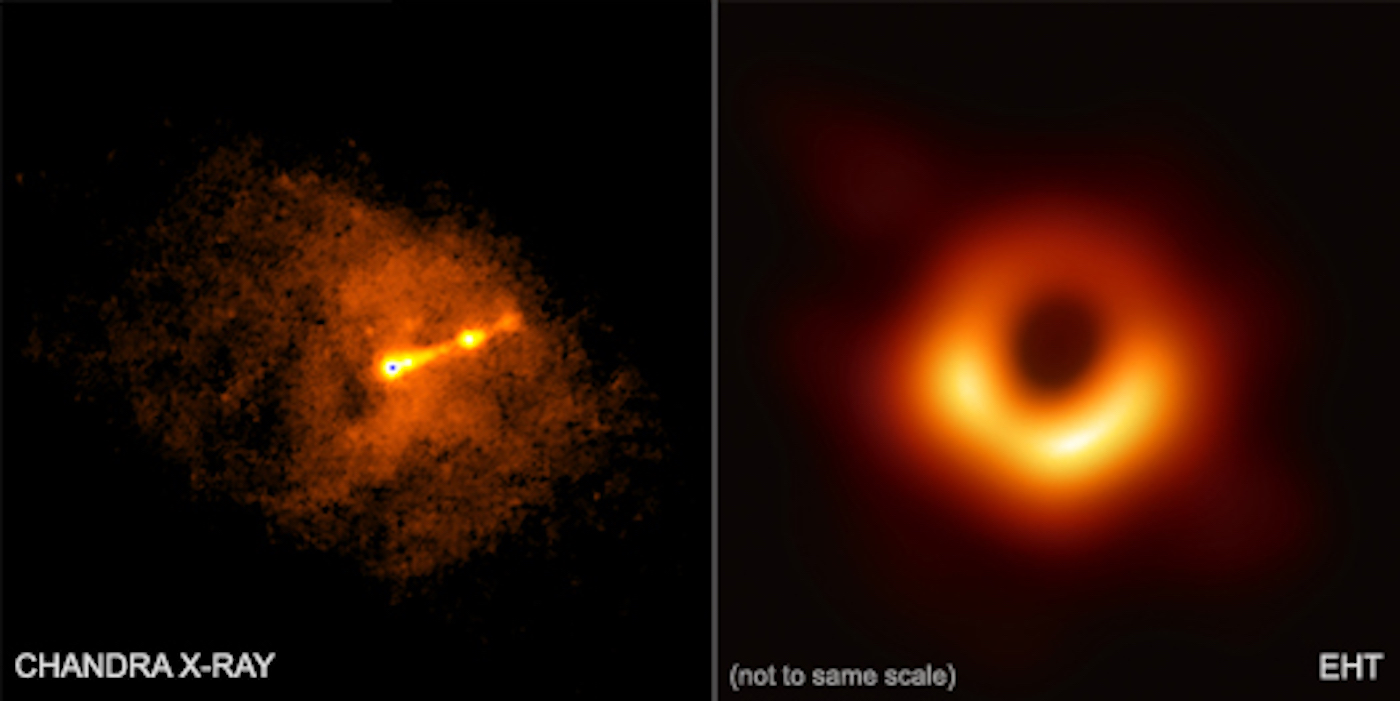

Outside the event horizon, swirling dust and gas form a disk of material, heated by friction to billions of degrees. Photons race around this horizon, trapped in an orbit we cannot see because the light never reaches us. A black hole devours material from its galaxy, and a border known as the event horizon marks the point of no return. Robert Oppenheimer and his students at the University of California, Berkeley concluded that massive stars could indeed collapse into a point of insurmountable density.Īround these black holes-a term popularized in the 1960s by the American physicist John Wheeler-space-time as we know it breaks down. But by the end of the 1930s, it didn’t seem so implausible. Einstein even tried later in life to prove that the so-called “Schwarzschild singularity” could not exist in nature. That was such a mind-boggling idea that Einstein himself was doubtful. He used Einstein’s equations describing general relativity-published only months before-to suggest that a star above a certain density would collapse into a point of infinite density and infinitesimal volume. The German physicist Karl Schwarzschild predicted the existence of black holes for the first time in 1915. Stitched together from several of the most powerful telescopes on the planet, the blurry image of darkness silhouetted by light is the result of decades of work by more than 200 scientists around the globe and coordinated by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. The picture again validated the physics of Einstein, but also provided a glimpse of what may lie beyond the universe we know. That image appeared in major newspapers around the world: a ring of superheated gas 55 million light-years away, about the width of our solar system, spiraling into an abyss with the mass of 6.5 billion suns at the center of the giant galaxy Messier 87 (M87). This past April, a picture of a black hole, captured by a global network of telescopes, again transformed our perception of the cosmos. By the 1960s, astronomers in New Jersey had detected radiation from the Big Bang, now called the Cosmic Microwave Background, marking the edge of the observable universe-though they didn’t know what they were seeing at first. In 1923, Edwin Hubble captured a pulsing star within the Andromeda Galaxy on a glass photographic plate, revealing for the first time that galaxies exist beyond our own Milky Way. One hundred years ago, astronomers captured the light of stars behind the sun during a total solar eclipse, proving that the sun had bent the starlight and validating Albert Einstein’s new theories of gravity. From time to time, a new picture of outer space changes our understanding of the universe and our place in it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)